With an estimated 100 million sharks slaughtered every year, we take a look at how countries’ practices and policies are impacting the shark fin trade in Asia

Text Hastings Forman

Shark fin – and shark meat – is widely consumed in Asia. Shark fin soup is a notable Chinese and Vietnamese delicacy: Such is the prestige associated with the cuisine that it is traditionally served at wedding banquets. At a restaurant, a single bowl can set you back USD100.

But over the course of the last two decades – with the help of big names such as Jackie Chan and Yao Ming, as well as hotel groups, restaurants and airlines – people all over the continent, particularly youth, are turning their backs on shark fin in the name environmental consciousness.

China, a large consumer, has notably banned the dish at state functions.

Shark fin soup can fetch around USD100 per bowl (Photo © Shutterstock)

A 2016 poll by WWF Singapore found that over three-quarters of Singaporeans want government policy to counter the consumption of shark fin. Similarly, a 2014 report by WildAid, an organisation that works to reduce demands for wildlife products, surveyed Chinese consumers online and found that 85 percent of participants had given up shark fin within the previous three years.

This signals a gradual cultural shift away from the traditional popularity and acceptability of consuming shark fin soup – and the statistics speak volumes. A 2013 report published in Marine Policy estimated that 100 million sharks are killed every year, although the figure could be anywhere between 63 million and 273 million.

The primary cause behind these shocking numbers? Overfishing for fins and meat.

What is Being Done?

“Pretty much every country in the world has banned shark finning, defined as the act of catching the animal, hacking off the fins, and discarding the body (many times while it is still alive) at sea,” says Randall Arauz, policy advisor of the shark conservation group, Fins Attached.

Fishermen can only dock with sharks that have their fins attached – to then be processed on land. But this is little more than a defence against a barbaric practice.

Arauz states that “in spite of the good intention, this regulation has done nothing at all to address overfishing… The requirement to simply land all the sharks caught is hardly a management policy, and it has no effect on population rebuilding”.

The danger of the shark finning industry is that of unsustainable fishing, threatening the existence of dozens of shark species and drastically reducing the overall population. “Sharks need a drastic reduction of fisheries-induced mortality,” affirms Arauz.

The requirement to simply land all the sharks caught is hardly a management policy, and it has no effect on population rebuilding. Sharks need a drastic reduction of fisheries-induced mortality.

-Randall Arauz, Fins Attached conservation group

But can countries counter the overfishing of sharks? Many nations have implemented restrictions on the trade of certain endangered shark species under the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) – if only partially. Others have taken further steps, banning shark fishing itself within their territorial waters. Indonesia has done so within Raja Ampat since 2010, and Palau has had a ban since 2009.

However, there can be a disconnect between policies that a nation adopts and their practical implementation. Paul Friese, founder of Bali Sharks Rescue Centre, notes that Indonesia – the top “shark catcher” in the world according to a 2011 analysis by TRAFFIC and the Pew Environment Group (PEG) – have “policies [that] don’t filter down to the fishing villages”.

Friese adds: “Fishermen don’t read newspapers, have Facebook or smart phones, for the most part.” The fact that many people are unaware of the rules means that “the disconnect from the policy makers to the fisherman is prevalent”.

Education on policies is an unresolved issue within Southeast Asian fishing communities. Yet Friese says that there are deterrents in place, notably for larger companies who acquire the majority of catches: “If commercial fisheries are caught, they get fines and penalties.”

In addressing these restrictions, Liz Ward-Sing from Shark Guardian, a marine conservation charity that conducts research projects, says: “We do not have data to show how shark populations have been affected by these bans [in relation to Asia and the rest of the world]. But we know that bans have had a positive effect long-term [on shark populations] in places like Palau.”

But Palau and Raja Ampat are just notable exceptions. It is very unlikely that more nations will implement full or temporary bans given feasibility issues – and money: There is still a high demand for shark fin, and countless businesses are invested in the industry, which generates significant revenue.

Fishermen don’t read newspapers, have Facebook or smart phones, for the most part… the disconnect from the policy makers to the fisherman is prevalent.

-Paul Friese, Bali Sharks Rescue Centre

Facing the Reality

In a simple dichotomy, there are nations that source the sharks, and nations that trade them. Regarding the former, national efforts to manage and regulate shark fisheries have really missed the mark – to such an extent, in fact, that they have led to the resounding failure of the plan for shark conservation by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), approved in 2001.

The TRAFFIC and PEG analysis from 2011 found that out of the top 20 “shark catchers” – who collectively account for 80 percent of the global shark catch – only 13 have implemented national plans of action to protect sharks – the FAO plan’s primary recommendation.

We do not have data to show how shark populations have been affected by these bans [in relation to Asia and the rest of the world]. But we know that bans have had a positive effect long-term [on shark populations] in places like Palau.

Even then, implementation is not always effective: Six out of the 20 nations have no breakdown of shark species when they are landed: Only eight provide data for a limited number of species, and 13 have no species breakdown. Without proper identification of species (and volumes) that have been caught and traded, we don’t know what and how much has been caught, where it has been caught, and where it will end up.

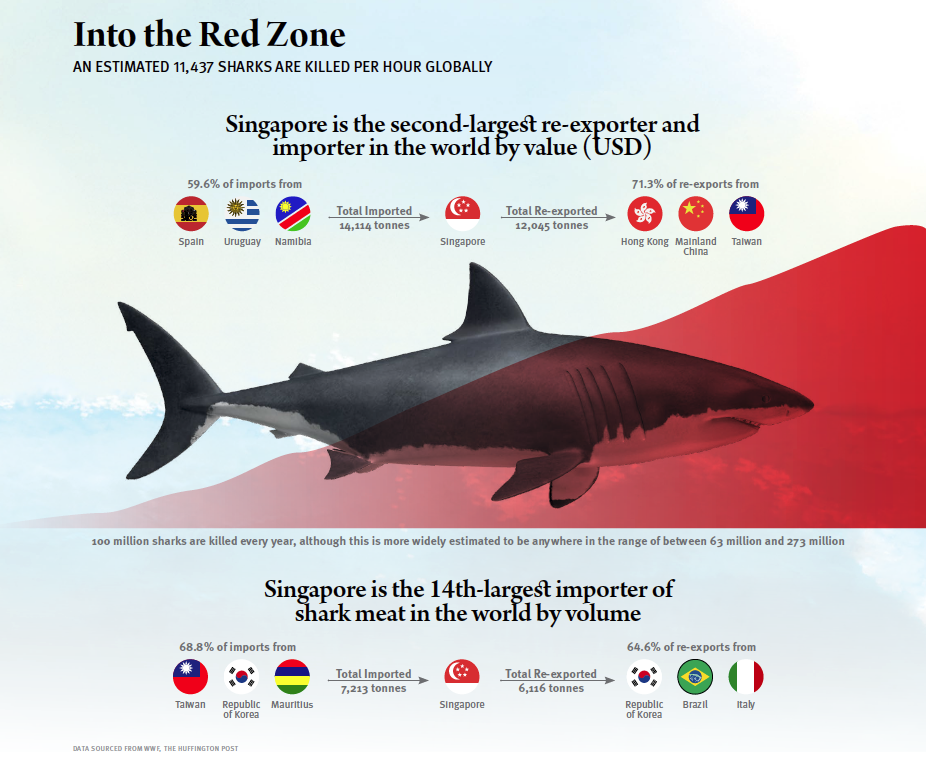

There is a heavy obligation on the shoulders of large trading nations. Despite the changes in attitude, a report by WWF and TRAFFIC this year found that Singapore remains the world’s second-largest shark fin trader by value, just behind Hong Kong. Singapore is also the world’s second-largest re-exporter of shark fin, accounting for 10 percent of global exports from 2012 to 2013.

In addressing this report, Ward-Sing says: “It’s not really a surprise to us. But it is very disappointing that such a developed, leading Asian country like Singapore is such a huge contributor to the shark fin trade. It shows there is still such a huge demand for shark fin soup in Asia and this is why we must continue our educational programmes worldwide to reduce the demand.”

Singapore would be expected to see large volumes of any product popular in the region come through its huge port. The same applies to Hong Kong, situated on the doorstep of a massive consumer, China.

It’s not really a surprise to us. But it is very disappointing that such a developed, leading Asian country like Singapore is such a huge contributor to the shark fin trade. It shows there is still such a huge demand for shark fin soup in Asia…

– Liz Ward-Sing, Shark Guardian conservation charity

Yet such major trading hubs can potentially have a positive influence – even more so if the local population is against the consumption of shark fin and wants to see their nation have more of an environmental impact.

“The fact that Singapore is a significant trader means the solution to the global shark crisis lies on our shores,” says WWF Singapore’s chief executive officer, Elaine Tan. As a feasible measure, WWF and TRAFFIC have recommended that Singapore Customs – and other nations – begin recording shark data with Harmonised System (HS) Codes (developed by the World Customs Organization and used to classify goods globally).

According to WWF-Singapore’s press release for the 2017 report, this would allow for detailed information about the trade: It would permit “distinction between dried and frozen shark products, which is critical for accurately determining actual trade volume, and [to] provide further insight into the species in trade”.

Transparency allows for nations to get to grips with sustainability – or at least begin to. Were such a system implemented, there would be monitoring of the volumes – and the species of sharks – being traded. This then allows control over the levels of trade to the benefit of sustaining shark populations.

The fact that Singapore is a significant trader means the solution to the global shark crisis lies on our shores.

– Elaine Tan, WWF Singapore

The Way Ahead

Perhaps one of the more obvious approaches to complement national efforts is to require the fisheries that source them to be verified as sustainable by a global organisation. The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), an international certification body for sustainable fishing, judges sustainable fishing according to measurements of healthy populations of species, as well as management measures that prevent overfishing and harm to the environment.

Elaine Tan from WWF says: “The development of sustainable fisheries for sharks is an important part of the solution to the shark crisis. But so far, only one shark fishery in the world has been certified sustainable by the MSC – for spiny dogfish in the US.”

Related: To Feed or Not to Feed?

Related: Ghost Nets of the Ocean

While this does illustrate certain problems – why would nations, especially developing ones, consent to sustainable standards and hurt their fishing industry? – it would undoubtedly be to the benefit of shark populations.

For now, at least, the road ahead for nations with large ports is to implement appropriate coding and to properly enforce their controls. In this way, unsustainable fisheries that target sharks indiscriminately (or seek to circumvent regulations) are cut off from exploiting the international market. Alongside education – from cities to isolated fishing villages – which will strengthen people’s resolve to get their nations to live up to international obligations, things may just start to change for the better for sharks.

From more stories on politics in Asia, see Asian Geographic Issue 04/2017 No. 126