by Asian Geographic Editorial Team

When examining Burmese politics leading up to the various coups, the impact independence leader Bogyoke Aung San had on Myanmar – and the subsequent fallout following his assassination in 1947 – cannot be understated. His death had profound implications for subsequent decades in Burmese history.

Hailed as the Father of the Nation, Aung San began his political involvement as a student, making a name for himself as a nationalist revolutionary who staunchly fought for Burma’s independence against British rule. He was one of the founders of the socialist Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and due to his pragmatic policies on the matters of foreign affairs, ethnic affairs, and the economic and social sectors, he enjoyed huge popularity among the people. Hence, despite his initial collision with the Japanese in a misguided bid to free his nation, Aung San was not tried in court following the defeat of Japan and the end of World War II.

ᐞ A photograph of General Aung San at his moment of triumph: At 10 Downing Street on January 27, 1947 to negotiate the independence of Burma from the British Empire. (To his left is his closest colleague in the talks, ICS U Tin Tut). He was then 31 years old. Image: lostfootsteps.org

Following the retreat of the Japanese, British rule was once again reinstated under Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith and talks of independence were pushed back in favour of political reconstruction. Naturally, this led to conflicts between the AFPFL and the British colonialists. With nationalist sentiment surging following the war, the AFPFL was becoming increasingly popular, making the political situation within Burma tenuous and British control unstable.

It should be noted at this point that prior to the war, not everyone in Burma was against British rule. It is imperative to understand that World War II drastically changed popular feelings towards the British. Prior to the British conquest, Burma had a long history of being under the rule of various Barma kings. The country comprised numerous divisive states, most of which were under the rule of the Barma people, which make up the largest ethnic group in Burma.

Prior to the arrival of the British, a wide variety of ethnic groups – the Arakan, Mon, Karen, Karenni/Kayah and Jingpaw Kachin – all suffered under the repression of the Bamar majority. Only smaller ethnic groups such as the Pa-O, Palaung, Kokang, Wa, Lahu, Lisu, and Lhaovo were spared from such treatment, ostensibly due to their distance from the capital.

During this period, British and American missionaries took the opportunity to inculcate these isolated ethnic minorities, drawing them away from animism and polytheism of the Bamar folk religion, and pushing them towards Christianity. Eventually, with the notable exceptions of the Shan, Mon, Arakan, and Bamar people, many ethnicities were converted.

ᐞ General Aung San shaking hands with British politician Arthur Bottomley at the 1947

Panglong Conference, Image: Wikipedia

When the British conquered the remains of Upper Burma in 1885 (known as the Third Anglo-Burmese War), these ethnic minorities welcomed them as saviours that were rescuing them from the despotic oppression of the Bamar kings. This acceptance and welcome of the British are important to note as while the Japanese occupation did change sentiment amongst most of the ethnic minorities, it did not change all of them. This, in turn, explains why the Karen and Mon minority opposed the Burmese Government after Burma’s independence from the British, leading to these groups’ involvement in the civil war of 1948.

Still, following WWII, Japanese oppression led to a sharp rise in nationalism in Burma, leading to an intense surge for self-determination. This manifested in the form of strikes. From late 1946 onwards, police in the capital, Rangoon, went on strike, a movement that would quickly gain momentum, spreading to government employees and eventually, leading to a mass strike. This forced the British governor at the time, Sir Hubert Rance, to meet with Aung San, inviting him, along with members of the AFPFL, into the Governor’s Executive Council. The Executive Council eventually gained more notoriety and power, allowing the Aung San-Attlee Agreement to be subsequently negotiated and signed in early 1947, laying down the terms for Burma’s independence.

Sentiment amongst most of the minority ethnic groups also began to change, aligning with the independence goals of Aung San and the AFPFL. With the realisation that even under the Aung San-Attlee agreement, the Frontier Areas (which were largely dominated by the minority ethnicities) would still be at risk of remaining under British dominion, ethnic leaders from the Chin, Kachin and Shan minorities agreed to sign the Panglong Agreement with Aung San in 1947. The agreement forged a united front to achieve independence from the British, leading to the formation of the Union of Burma in early January 1948.

ᐞ General Aung San signs the Panglong Agreement on February 12, 1947 Image: Wikipedia

Hence, Aung San was instrumental in the push for independence from the British and negotiations for the extension of federal rights for ethnic minorities following independence. Tragically, he was assassinated before he could witness his dream come to fruition.

Aung San’s assassination came as a shock for most of the populace but was ultimately the result of brewing fractionalisation within the AFPFL, a coalition of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), the Burma National Army and the socialist People’s Revolutionary Party (PRP), formed in response to the Japanese occupation. Aung San led the party during and after the occupation, but following the end of the war, disagreements emerged between AFPFL’s leading members. This subsequently led to the resignation of CPB leader Than Tun and the expulsion of his party.

Following their successful negotiations of both the Aung San-Attlee Agreement and the Panglong Agreement, the AFPFL, which was now dominated by Aung San and the socialists, won the 1947 constituent assembly elections, effectively making them the new ruling party of Burma. Displeased by the power they held, U Saw, Prime Minister of British Burma and leader of a rival political group, planned the execution of Aung San and other independence leaders. U Saw would hang for the crime less than a year later.

Following Aung San’s death, U Nu, Vice Chairman of the ruling AFPFL and Speaker of the Constituent Assembly of Burma, succeeded as Prime Minister under fraught circumstances. With the infighting in the AFPFL intensifying following their leader’s death, parliament was thrown into chaos and U Nu barely survived a no-confidence vote. To salvage the situation, he decided to invite Chief of Staff General Ne Win to form a caretaker government with him, designed to last until 1960.

ᐞ U Nu

Under U Nu, Burma gained independence from the British on January 4, 1948. Unfortunately, without the leadership of Aung San, several opposition groups began capitalising on the AFPFL’s weakness, outright challenging them, and plunging Burma into a state of unrest – a civil war – just eight months after independence.

Chaos broke out between various ethnic groups and the government. Between 1948 to 1950, the Karen and Mon formed armed groups and fought with the armed forces of the AFPFL government. A communist insurgency against the AFPFL was also waged by the CPB, also called the “White Flags”, and another communist party, known as the “Red Flags”.

With so much conflict both between factions and within the party, General Ne Win and the armed forces were able to extend their influence in the country – not only in the political realm but in the economic sector as well. Taken together, this laid the groundwork for the military to stage their 1962 coup d’état, ushering in decades of political dominance of the army in Myanmar.

When we look back at the first military coup that occurred in Burma in 1962, we need to understand that the political sensibility of the Bamar majority was not very developed at that time, especially around matters of democracy, federalism, economic development and eradicating corruption. The Burmese were more focused on achieving independence from Western powers and were less concerned about democratic values and the need for a democratic system.

Thus, when Ne Win seized power, there was little resistance on all fronts. In the political realm, parties on both the right-wing and left-wing mostly welcomed the coup, as Ne Win promised to guide the country towards the “Burmese Way to Socialism”. Similarly, most civilians did not have a fierce resistance to the military takeover, preferring discipline and stability over freedom under democracy.

The public generally perceived the elected civilian government as incompetent, corrupt, and incapable of restoring law and order, while the military seemingly offered the social stability so necessary after the difficult years following the war. With its socialist policies prioritising agriculture over the industry, the military even improved the living standards of the Burmese, the majority of whom were peasants, at least initially. International actors also had no objections to the coup. If anything, the military rulers’ anti-communist stance was a boon for countries such as the United States, which was in the midst of the Cold War.

Ultimately, the only resistance against Ne Win and his overthrowing of the government was from the armed groups of ethnic minorities, two communist armed groups, and students from Rangoon University. The students, protesting strict new campus regulations and the end of the system of university self-administration, led a series of marches and demonstrations that were finally violently crushed by military forces. Thousands were arrested and more than 100 students were killed.

Despite the support by the overwhelming majority of Burmese, it didn’t take long for the military to squander citizens’ goodwill. Its leaders knew little about the intricacies of running a country, much less about instituting a proper financial system, and money supply and inflation rose uncontrollably as the regime printed money endlessly to fund its political goals.

In their first misguided effort to stem rising inflation, in 1964, the generals decided that 50- and 100-kyat notes would cease to be legal tender overnight, an attempt to wipe out the purchasing power of “foreigners and evil capitalists” determined to embarrass and destabilise the economy. People were required to surrender the banknotes to centres around the country with the promise of reimbursement, but the process ultimately broke down, with many rural Burmese failing to change their notes. Unsurprisingly, the move punished ordinary citizens, ruining countless small businesses and destroying confidence in the kyat. Inflation continued to rise.

Unfortunately, the military regime learned nothing from the failed demonetisation of 1964, and two decades later, the regime once again attempted to rein in what is perceived as the “unscrupulous” economic activities of its political enemies. In 1985, 20-, 50- and 100-kyat notes became worthless overnight, and while exchanges were again promised, it is estimated that authorities only reimbursed a quarter of the value of the notes surrendered. New notes in bizarre denominations – 25, 35 and 75 kyat – were subsequently printed at a record pace, and inflation rose unabated.

ᐞ The bizarre demonetisations in 1985 and 1987 were meant to end profiteering and the black market, as well as cripple insurgents. The result was economic chaos.

Shockingly, two years later, in 1987, General Ne Win suddenly announced that the recently introduced 25-, 35- and 75-kyat notes would be scrapped. At that time, these banknotes accounted for nearly 80 per cent of the money in circulation in Myanmar, and this time around, the regime offered no reimbursement. The economic hardships and political repression that followed fuelled renewed anti-government sentiment, and by March 1988, the country fell into chaos, violent protesters demanding a new government that could fix the economy and set the country on a path to democracy.

In July 1988, Ne Win suddenly resigned as chairman of the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP), the party established by the military that had ruled the country since the 1962 coup. During his resignation speech, Ne Win reminded the country of what the military was capable of:

“When the army shoots, it shoots to kill.”

– General Ne Win

ᐞ Myanmar pro-democracy activists hold placards during a rally against the country’s military junta near the Myanmar embassy in Seoul on August 8, 2009. A group of some 30 activists demanding the opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s immediate release, staged a protest to mark the 21st anniversary of the 1988 pro-democracy uprising, which ended in a massacre by Myanmar government troops

The protests, now known as the “8888 Uprising”, reached their peak in August 1988 and resulted in a brutal crackdown by the military, led by General Saw Maung, resulting in the death of thousands. After the demise of the BSPP, the military once again took control of the country, but the junta finally agreed to a shift to a multi-party system.

Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) would go on to win the 1990 election by a landslide, but the military refused to recognise the results, and another 20 years of military rule would ensue.

ᐞ Aung San Suu Kyi, the National League for Democracy (NLD) leader, 1989,

Image: politics-history.mozello.com

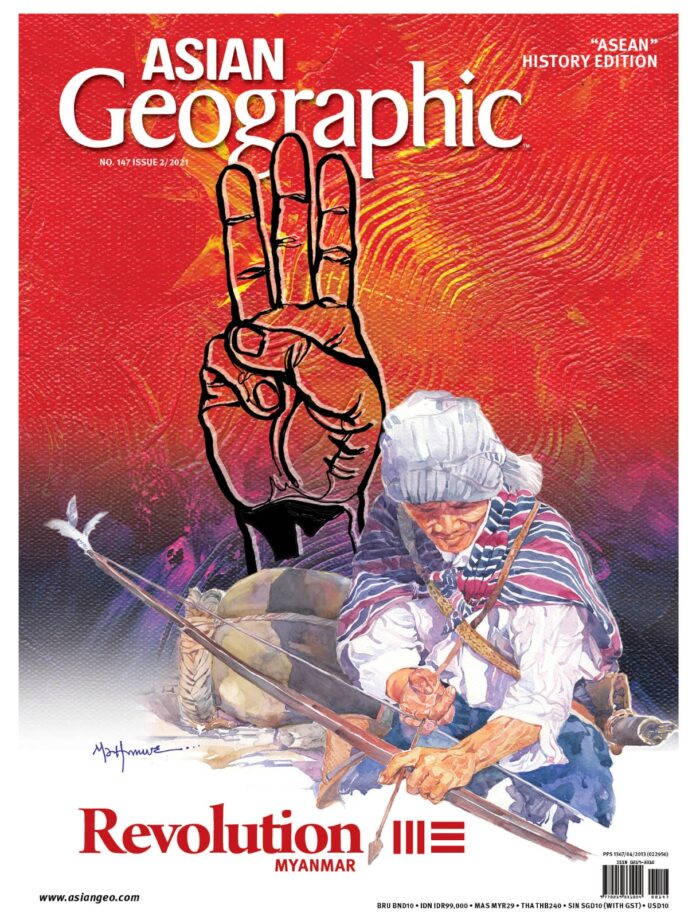

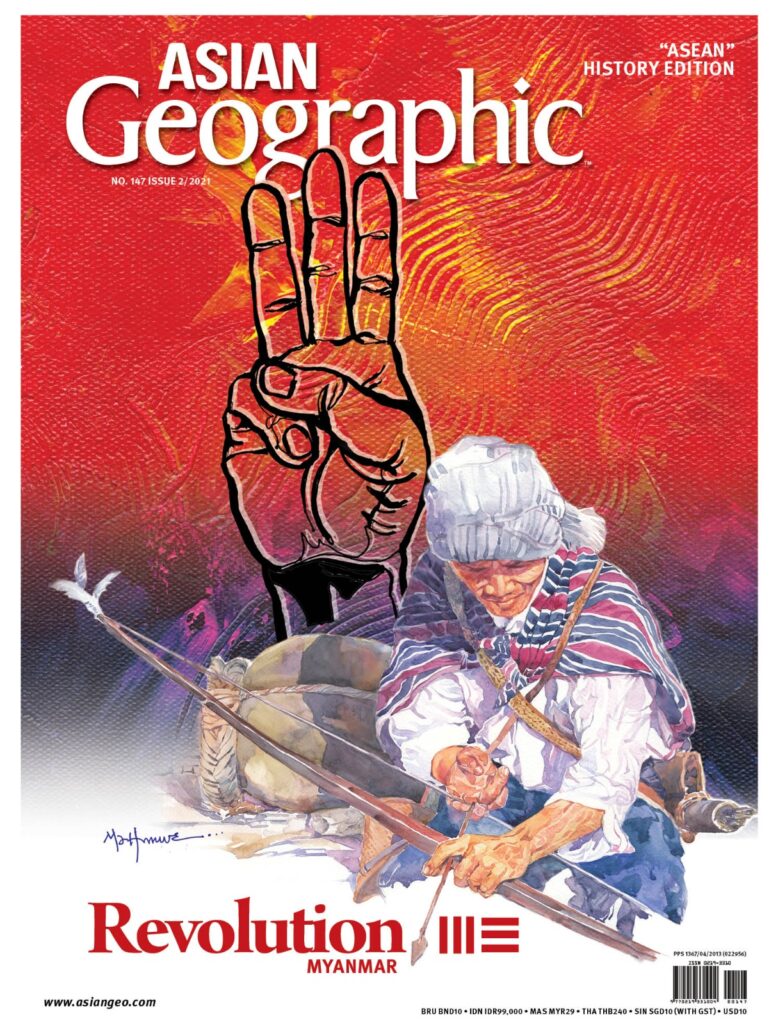

Read more about Burmese History and the lead-up to the 2021 protests in Myanmar, check out Asian Geographic Magazine Issue 2/2021 coming to the shelves soon or reserve your copy by emailing marketing@asiangeo.com.

Read more about Burmese History and the lead-up to the 2021 protests in Myanmar, check out Asian Geographic Magazine Issue 2/2021 coming to the shelves soon or reserve your copy by emailing marketing@asiangeo.com.

Subscribe to Asian Geographic Magazine here or for more details, please visit https://www.shop.asiangeo.com/