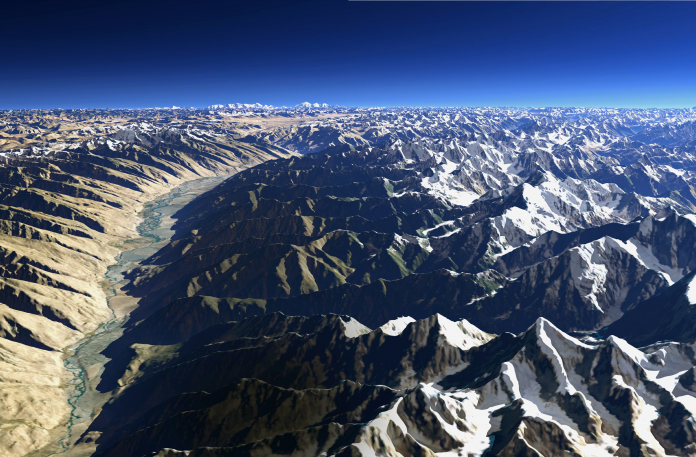

Sandwiched between the mountains of the Hindu Kush and Karakoram, the Wakhan Corridor linking Afghanistan and China played a vital role in the 19th-century battle for control in Central Asia. Today, devoid of electricity and all extravagance, the Wakhan is a window into history centuries ago.

Text by Sophie Ibbotson & Max Lovell-Hoare

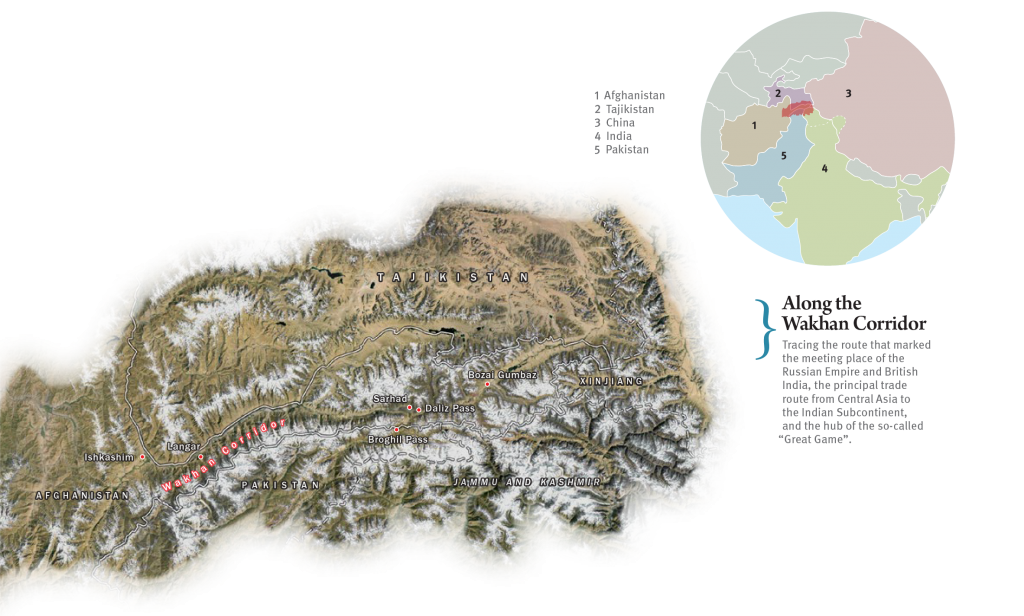

There is a far, forgotten corner of Afghanistan where foreigners need not fear to tread. Some 100 years or so ago, this narrow sliver of territory, which juts out like a finger pointing straight at China, was central to the political and economic concerns not just of Afghanistan, but of the world. It marked the meeting place of the Russian Empire and British India; the principal trade route from Central Asia to the Indian Subcontinent; and the hub of the so-called “Great Game”, where spies, explorers and military officers danced in diplomatic shadows.

More than a century on, the Wakhan Corridor is all but neglected, and in terms of security at least, that’s a good thing. The Soviet war in Afghanistan, between 1979 and 1989, left little behind, save some long-abandoned hardware, and the Taliban remained largely in their traditional heartlands in the country’s south. Few people made the arduous journey on foot to the wildlands in the north. Now, only Wakhi and Kyrgyz nomads drive their flocks here, spurred on with the help of the Aga Khan, spiritual leader of the Ismaili community and, at least where rural schools and community centres are concerned, miracle worker.

More than a century on, the Wakhan Corridor is all but neglected, and in terms of security at least, that’s a good thing. The Soviet war in Afghanistan, between 1979 and 1989, left little behind, save some long-abandoned hardware, and the Taliban remained largely in their traditional heartlands in the country’s south. Few people made the arduous journey on foot to the wildlands in the north. Now, only Wakhi and Kyrgyz nomads drive their flocks here, spurred on with the help of the Aga Khan, spiritual leader of the Ismaili community and, at least where rural schools and community centres are concerned, miracle worker.

We first came to the Wakhan in June 2010, taking a brief diversion into the valley while delivering aid vehicles from London to Faizabad, Badakhshan. This first glimpse set in motion a yearning to discover what lay beyond the cragged horizon, nestled betwixt the snow-capped Pamir and Hindu Kush, and so a year later, we returned to follow in the footsteps of some of the 19th century’s greatest explorers.

These days, all journeys in the Wakhan begin in Ishkashim, the border town that straddles the Panj River (the Oxus of antiquity), a bridge linking Afghanistan with its northern neighbour, Tajikistan. Passes into China – which archaeologist and explorer Aurel Stein recorded 100 laden ponies crossing when he visited in 1906 – are now closed to foreigners, as is the way to Chittral in northern Pakistan. Those on the Afghan side gaze longingly at the tarmac roads and twinkling lights of Tajikistan; car batteries and the occasional generator are the only sources of electricity here.

The Panj River is central to the Wakhan and its history. It has carved the valleys and irrigates the small patches of cultivated land along the valley floor. The search for the river’s source brought a succession of British explorers, Lord Curzon (later Viceroy of India), Lieutenant Colonel Sir Francis Younghusband, Lord Dunmore, Lieutenant John Wood and Colonel Trotter amongst them. To walk in the wilds of the Wakhan is to walk in the footprints of history.

From Ishkashim, we drove our battered Land Rover to Sarhad-e Broghil, at the end of what passes for a road in the Wakhan. Constructed in the 1960s, it is a road in the very loosest of senses: travelling the little more than 80 kilometres along its length takes a full day of driving, broken dirt track interspersed with gravel riverbed and several river crossings. Even in September, when the rivers are low and the waters as yet unfrozen, it’s an exhausting, bone-shaking drive, though undoubtedly preferable to crossing the same terrain on foot.

The road, such as it is, peters to a halt at Sarhad, however, and from there on the only way is on foot. In his journal, Aurel Stein wrote, “Between Sarhad and the stage of Langar the valley contracts into a succession of defiles difficult for laden animals in the spring, when the winter route along the river bed is closed by the floodwater, while impracticable soft snow still covers the high summer-track.”

Nothing has changed at all. The narrow pathway – first across the 4,267-metre Daliz Pass, which we crossed panting and wheezing thanks to poor fitness and altitude, and then winding its way to the smattering of mud huts at Langar, used as rest stops by shepherds moving their flocks – clings to precipitous rock. Though one or two wooden footbridges have been built, they scarcely look capable of taking a man’s weight, let alone that of a pony weighed down with packs. The days are bright, but there’s ice on the tents in the early morning, despite it being late summer, and even a smattering of snow now and then.

It’s not until the fourth day of walking that we see signs of permanent human habitation: a solitary yurt, a family and their herd of yaks. Life in the Wakhan is unbelievably tough – life expectancy is just 45 years – but the family is hospitable, welcoming us inside for steaming tea in porcelain bowls, sweetened with a little sugar, and large, flatbread that is softer if you dip it in the tea. Looking at their simple belongings, it’s hard not to think back to Curzon and his entourage who came here searching for ice caves in 1894. They too carried everything with them, but unlike the modern traveller, Curzon felt it essential to carry his own collapsible rubber bath. Whether he was ever able to heat enough water to use it, however, remains one of the Wakhan’s enduring mysteries!

We reached Bozai Gumbaz by mid-afternoon, the red dresses of the Kyrgyz women standing out strikingly against the greenish-grey of the surrounding landscape. This was where Francis Younghusband met the Russian Colonel Yonoff in the early 1890s, sharing champagne, caviar and three days of frivolity before sparking the so-called Pamir Incident and narrowly avoiding war. Our meals were far more meagre pickings: dried fruits and nuts purchased in Khorog before leaving Tajikistan, army-style ration packs and plenty of stodgy porridge.

Though the landscape and yurts remain unchanged, there is one important development here: in 2011, the Central Asia Institute built a school. Made famous in Greg Mortenson’s Stones into Schools, this is the first time that local children have had access to education. In three simple classrooms, teachers give lessons in Persian and English; the curriculum includes maths, sciences and literature.

The Wakhan Corridor may look more or less as it has done for centuries, but change is on the way. There is talk of a road to China and a reopening of the Broghil Pass to Pakistan. If you look closely, you’ll already spy occasional solar panels and mobile phones (albeit without network coverage). The children, once educated, will ask for something more than eking out a life at the end of the world. If you want to see the Wakhan as a wilderness, now is the time to go. The world can change in a heartbeat, and once the Wakhan’s potential is exploited, the traditional Wakhi way of life will quickly disappear.

Check out the rest of this article in Asian Geographic No.102 Issue 1/2014 by downloading a digital copy here. And subscribe here!