A photographer’s account of the Kowloon Walled City before its demolition in 1993

by Greg Girard

Travellers lucky enough to have flown into Hong Kong’s Kai Tak Airport before it closed in 1998 will know that the final approach was one of the more thrilling moments in modern air travel. The aircraft would descend low over the densely-populated and heavily built-up Kowloon peninsula, aiming for a large orange and white checkerboard painted on the side of a hill.

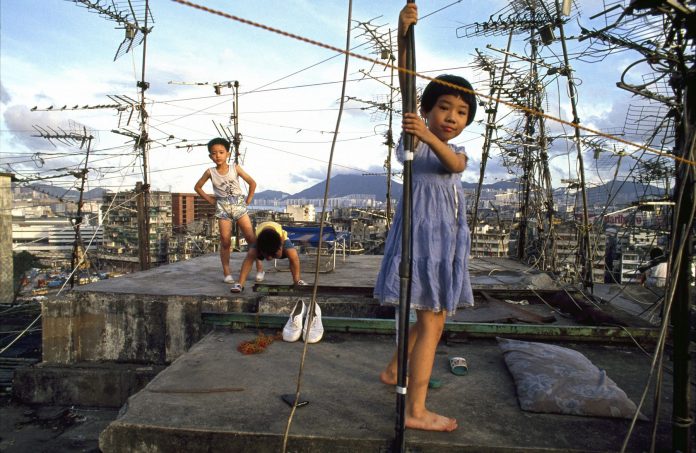

The pilot would then execute a 47-degree right turn, giving passengers a heart-stopping view as the wing dipped down and sliced past rooftops full of laundry, TV aerials and neon signs, before levelling out below 200 feet to line up with the single runway jutting out into the oily waters of Kowloon Bay. Landings were often hard and accompanied by an outburst of clapping from relieved passengers.

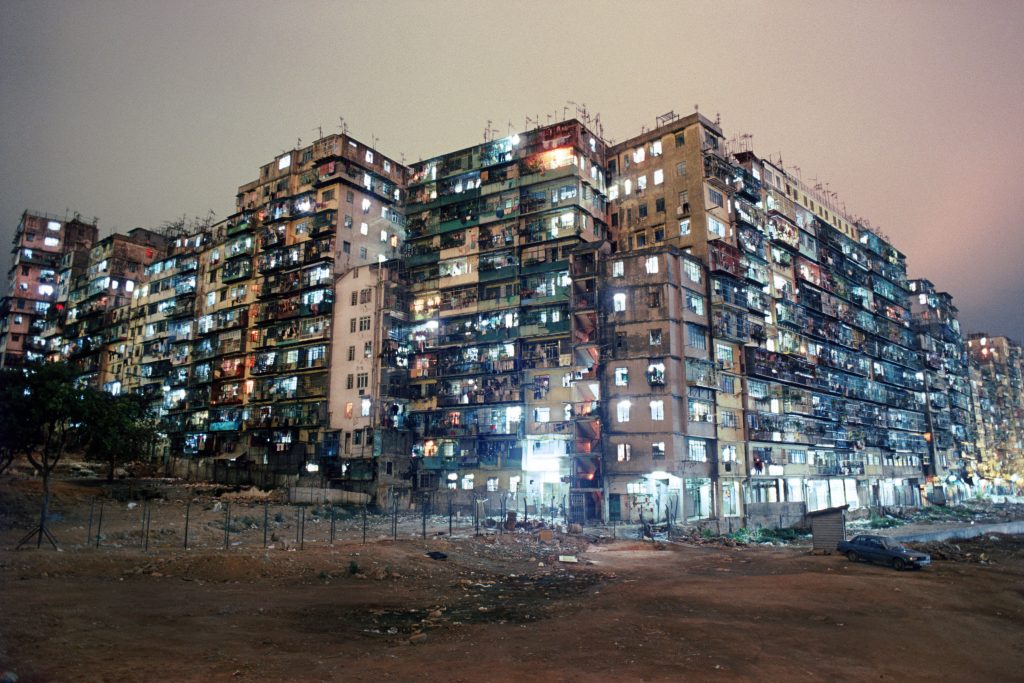

Passengers on the left side of the aircraft were provided a different, though no less extraordinary view. If you knew what you were looking for, you would have been able to pick out a large, strange, almost medieval-looking structure as it flashed by below, just three blocks from the end of the runway.

This was the closest most people ever got to the Kowloon Walled City – 300 interconnected high-rise buildings, built without contributions from architects or engineers, home to nearly 40,000 people. This was the most densely-populated place on the planet. Technically, it was a piece of sovereign Chinese territory in the middle of British-administered Hong Kong, though at the time almost no one knew any of these facts, including me.

Discovering a “building-thing”

Living in Hong Kong in the 1980s I had heard about the Kowloon Walled City. Almost everyone had. It was rumoured to be a dangerous area controlled by triad gangs – a place where the police didn’t venture. But I had never been there nor ever seen it, even in photographs. And I certainly knew nothing of its strange and complicated history. I “discovered” it one evening while photographing in the streets near Kai Tak Airport. Turning a corner I was stopped in my tracks by a building at the end of the block that looked completely out of place. “Building” isn’t quite the right word. It was more of a “building-thing”. It looked like what a building in a crowded city might look like if there were no rules, no regulations and no laws governing buildings and their inhabitants, which of course is exactly what the Walled City was.

It was quite literally a place where Hong Kong’s laws didn’t apply. There was a clause in the treaty between Britain and China that exempted a lone Qing Dynasty magistrate’s compound on the Kowloon peninsula from British control. This fortified enclosure effectively became a tiny piece of sovereign Chinese territory in the middle of the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong – a distinction that, for the most part, meant that it was essentially ignored by all parties, including the local Hong Kong administration. This anomalous remnant thus earned the description of a “triply neglected” place.

A city within a city

Over the years this small enclave evolved and mutated in administrative limbo – from a single-story settlement populated by squatters, to a destination for refugees coming out of mainland China in the 1950s and 1960s, to a vertical home-made “city within a city” where more than 35,000 people lived and worked, crammed into a single city block. It was this latter, final version of the Kowloon Walled City that I got to know something of.

I didn’t make any pictures that first night I came across it but little by little I started exploring the Walled City. Its “streets” were narrow openings between buildings. They led into its dark interior where they were intersected by other even narrower lanes leading deeper into the “city”. These lanes were mostly covered overhead by a network of piping and electrical wires, clogged with garbage thrown from upper floors and dripping from accumulated rainwater.

Workshops and businesses lined the lanes – barbecue meat factories, dentists, noodle-makers and small plastics factories with stairways every few metres leading to upper floors. Workers passed by in the alleys carrying pig carcasses or sacks of flour or pails of fish balls. But you also saw school children on their way to or from school or a postman delivering the mail – scenes of “normal” life in other words.

Up until that time anything written about the Walled City had always portrayed it as a slum and a drug-infested, gangster-controlled ghetto. And although it certainly was a slum, it was clear that most people were simply trying to lead ordinary lives under extraordinary conditions. Little by little I started trying to make pictures of the people and the place to show its extreme physical compromises, but also the variety of life and work that went on there.

Photographing the people

Certainly, in the beginning, there was resistance to an outsider with a camera. Most residents believed, judging from their past experience with reporters and photographers no doubt, that I was just one more person there to show how miserable the place and its residents were, so you could hardly blame them for their initial hostility. That all changed however when in 1987 the Hong Kong government announced that the Walled City was to be demolished and its residents resettled. A deal had been struck between London and Beijing and with its days numbered, residents implicitly understood that I was there to photograph the Walled City before it disappeared, and from then on the process became much easier.

Around this time I met Ian Lambot, who was also photographing in the Walled City. Ian had trained as an architect and his approach was mostly to examine this extraordinary place as an architectural phenomenon. I was mostly interested in photographing the people and how they lived. Our different approaches were complementary and we teamed up to work towards publishing a book.

We were both interested in presenting the Walled City as a functioning community, a place that despite its many compromises not only worked but worked well – taking full advantage of the lack of government oversight of course. For example, a builder might erect a building, but rather than provide his own staircase he might strike a deal with a neighbour and simply punch out the wall of an adjacent building and use its staircase instead.

Food factories functioned without health or safety inspections but were well-patronised by customers both inside and outside the Walled City. Doctors and dentists who had trained in mainland China were unable to practice in Hong Kong without being certified by the territory’s regulatory authorities, and so due to the lack of oversight, medical and dental care was provided at lower rates inside the Walled City than in Hong Kong proper with patients visiting from all over the territory.

Over a five-year period (1987-1992) we came to know many of the Walled City’s residents and learned to navigate its alleys, stairways and rooftops. Not everyone allowed us into their homes and workplaces but certainly many more people opened their doors than closed them.

Ian and I published our first book, City of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City, in 1993, the year the Walled City was demolished. The book remained in print for nearly 20 years, until we expanded and updated it, releasing City of Darkness Revisited in 2014.

The new book adds information that wasn’t available earlier and traces the unexpected ways the Walled City has come to influence popular culture, architecture and urban studies so many years after its demolition. We also address the many myths that continue to swirl about relating to drugs, gangs, policing and other facets that continue to shape the Walled City’s “noir” reputation.

Strange, magnificent and defiant

I am sometimes asked if I think the Walled City should have been saved or preserved in some way. Earlier on, with the memory of its difficult conditions (including smells) still fresh, I always answered “no”. The place was a fire, safety and health hazard and you couldn’t expect people to live like that. And to somehow bring it up to “code” would not only have been impossibly expensive but would have neutralised all that was strange, magnificent and defiant about it.

These days, however, I’m not so sure how to answer. Perhaps “something” representative should or could have been preserved. What and how exactly I can’t say – perhaps a typical apartment which also served as a workshop, where a family of four lived and worked in less than 100 square feet. Today, a rather unremarkable park occupies the former site of the Walled City. One of the original Qing Dynasty magistrate’s buildings has been retained and some unfortunate faux structures were added when the park was completed.

When the Walled City was demolished in 1993, Hong Kong was a place that didn’t look backwards. That has changed in recent years. The change is a generational one, with a new appreciation of Hong Kong’s history and architectural heritage. Unfortunately, the change has happened too late to preserve some physical reminder of what life was like in one of Hong Kong’s most notorious, unique and deeply misunderstood communities. Visitors to the Kowloon Walled City Park, however, may be able to hear first-hand accounts from former residents who sometimes gather at the park and share stories of what life was like in one of the most crowded places on earth.

For more stories and photos, download a digital copy of Asian Geographic No.115 Issue 6/2015 here!