(Text by Dr Craig Turner)

IF you want to see primates in Asia, then Sri Lanka may not immediately come to mind. But if it’s something different you’re after – a more ancient form not merely monkeys or apes – then India’s diminutive neighbour should be your destination of choice. Researchers are currently unravelling the secret life of a primitive prosimian primate – the red slender loris, Loris tardigradus.

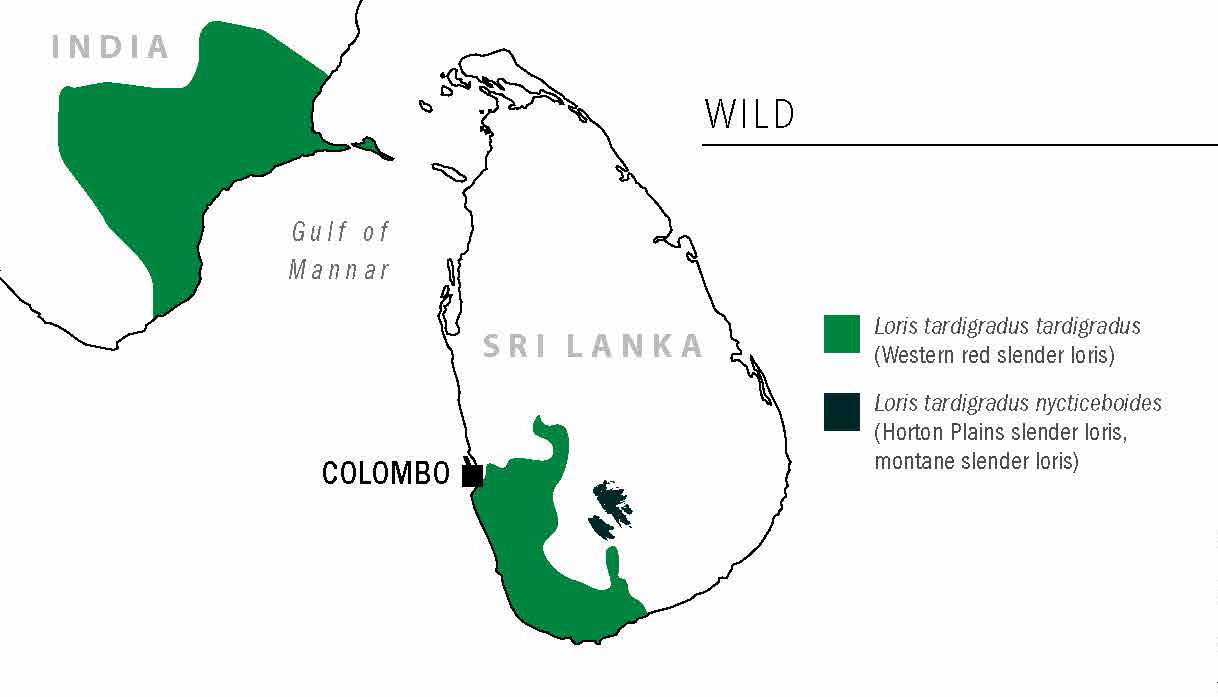

The fauna and flora of Sri Lanka are generally considered an extension of that of the Western Ghats, in southern India, and together the two areas constitute a single biodiversity hotspot. Yet the wet evergreen forests of these nations each have distinctive endemic species, and the red slender loris is a prime example that is unique to Sri Lanka.

Visitors to this island nation may be more familiar with its more obvious and charismatic wildlife – its celebrated birds, famous elephants and elusive leopards. Primates may just represent a bonus encounter. The five species of non-human primates that are found in Sri Lanka are split into two groups. The first is the haplorrhines (meaning “dry-nosed”), which broadly covers the “monkeys”: the toque macaque (Macaca sinica), purple-faced langur (Trachypithecus vetulus) and the grey-handed crested langur (Semnopithecus priam thersites). Active by day, they are relatively easy to find.

The EDGE (Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered) of Existence is a pioneering initiative offering a new method of prioritising global conservation efforts. It is the first project focusing on the conservation of the world’s most threatened species that takes into account the evolutionary relationships between species. The EDGE list contains the planet’s most extraordinary endangered species, but most are not currently receiving conservation attention. edgeofexistence.org

[/ultimate_ctation]

The second group is the (“moist-nosed”) strepsirrhines, comprising Loris tardigradus and Loris lydekkarianus, the grey slender loris. Their sharpened sense of smell and enormous eyes (containing a reflective layer) – along with a unique “toilet” or grooming claw – all distinguish them from monkeys. They are nocturnal and shy, and consequently much harder to spot. Unfortunately, they are also known to be endangered. Yet our knowledge of these diminutive, wide-eyed primates is relatively limited considering they have been lurking in our forests for the past 20 million years.

INFO

Scientific name: Loris tardigradus

Common name: Red slender loris

Sub-species: Loris tardigradus tardigradus (western red slender loris), Loris tardigradus nycticeboides

(Horton Plains slender loris, montane slender loris).

Biology: Loris are characterised by a small, long and slender body, with a rounded head and a short, sharp muzzle. Average body weight is 165g. Its fur is woolly, but its wet nose, the tips of its ears, palms and sole (except the heel region) are naked. Its eyes are very large and closely set, with moderately large, almost naked ears. The tail is absent and the limbs are very long and slender. Montane slender loris have greater body mass (220g), shorter limbs and longer, dense fur.

Lifestyle: They are the only nocturnal primates in Sri Lanka. They are predominantly arboreal and highly sensitive to forest loss or modification.

Communication: Lorises communicate via olfactory means, using “urine marking” and “urine washing”, and they also vocalise using a range of whistles, chitters, growls and screams. These communicate location to friendly conspecifics, warnings to non-group members, and females use them to ward off encroaching males. Vocal battles are common.

Diet: Loris tardigradus has only been observed to eat animal prey. Although they will eat fruit in a captive setting, they will always choose animal prey first. In addition to insects (moths, stick insects, dragonflies, beetles, cockroaches, grasshoppers), they are known to relish lizards and geckos.

Breeding: Copulations can occur after play wrestling but most often commence after many males have pursued a female. Dominant males may form partnerships with smaller-bodied beta males. These male coalitions work together to pursue oestrous females. The gestation period is 165–175 days. Births occur throughout the year with no evidence for a birth peak. Although singletons are more common, this subspecies also gives birth to twins. Average lifespan is 12–15 years.

Distribution: The genus is confined to Sri Lanka

and parts of Southern India. The red slender loris is endemic to central and southwestern Sri Lanka, and is typically found in the southern “wet zone” of the island, up to the central “intermediate zone”.

Conservation status: (IUCN Red List) Endangered

Population trend: All populations are thought to be in decline.

[/ultimate_ctation]

The life of these mysterious animals is only now slowly being revealed as they find themselves the subject of a large-scale study being undertaken by a dedicated team of Sri Lankan field researchers trained by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). The group, from the University of Colombo and the Open University of Sri Lanka, is working in collaboration with the ZSL’s Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) programme (edgeofexistence. org), trying to answer the “what” and “where” of the loris world, across Sri Lanka.

The ZSL has ranked the species 22nd, in terms of conservation priority, on a list of over 4,000 of the world’s most threatened EDGE mammals. It has also established that the red slender loris has been overlooked by most major conservation initiatives and could be silently slipping unnoticed towards extinction.

The project is one of the first large-scale biodiversity assessments to be undertaken in Sri Lanka. Saman Gamage, who leads the field research programme, says,“We have completed over 1,000 night-time surveys across much of the wet and intermediate zones of southwestern Sri Lanka.” This has meant walking over 2,000 kilometres in the dark assessing their “occupancy” in over 120 different fragmented forest patches.

Field research continues apace, limited only by available funds. Conservation attention has already been focused on the Horton Plains slender loris, and a reforestation project is due to begin with the aid of the BBC Wildlife Fund. This is progress, but celebrations would be premature. When you are trying to ensure the survival of 20 million years of Sri Lankan natural history, it truly is a race against time. AG

Read the rest of this article in No.82 Issue 5/2011 of Asian Geographic magazine by subscribing here or check out all of our publications here.