A Basic Survival Kit

By YD Bar-Ness

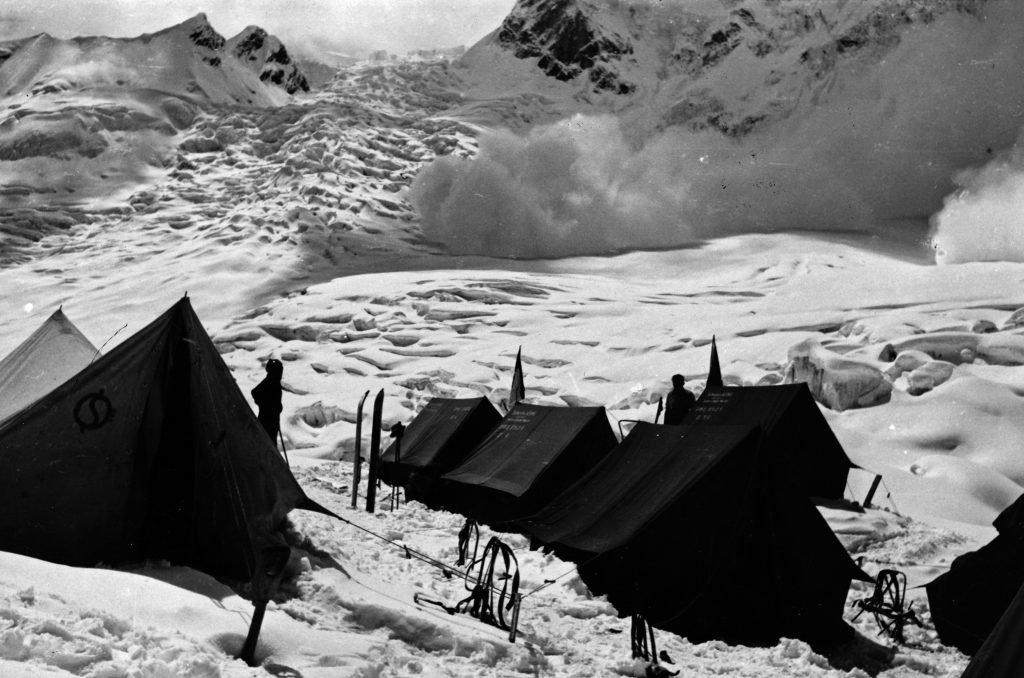

I first learnt of avalanches and their dangers on a hot summer’s day, eager and ready to climb a volcano. There on the flanks of the mountain soaring above us, the icefalls and glacier mass glinted in the sun. Slightly brighter, but less crystalline, the fresh snow of the last few days decorated the mountain in an uneven coat.

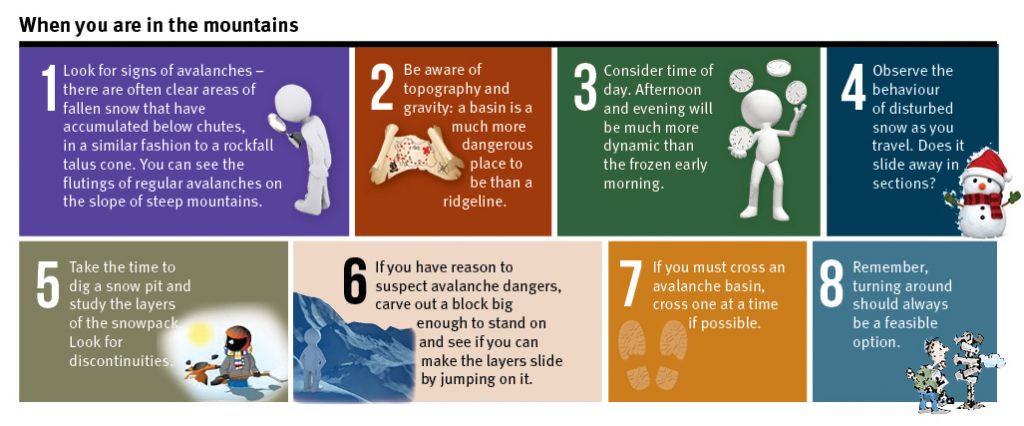

Avalanches had, until then, seemed like such an abstract concept, but we could see the conditions clearly: there were loose slabs of snow hundreds of metres long, clearly delineated by cracks and poised to slide down and bury anything below. We didn’t need to see the slabs themselves, however, to know that the risk of avalanches was high. Weather and terrain conditions guided our decision, as well as some official advice from the local government. We had read the avalanche report. What were the conditions that led to this assessment?

Snowpack and Layers

If a glacier is the frozen equivalent of a river, then an avalanche is somewhat like the flooding torrents that blanket the slopes. Unlike water, however, snow will stay in place and not immediately race down to the lowest point on the landscape. A given quantity of snow can pile up onto itself and will eventually melt, evaporate, or accumulate as glacier ice. This pile is known as the snowpack, and it can have layers just like sandstone or tree rings. It can also differ dramatically in composition within a short distance. Plus, the windward side of the mountain summit can have a very different snowpack than in a ravine lower down.

These layers in the snowpack record the conditions of snowfall, and snow is an infinitely variable thing. However, there’s no promise that the pile will stay in place – especially when it has settled onto a tilted portion of land. If one of these layers does not stick to the one beneath it, then the snowpack can slip off as an avalanche.

This slippery layer is often associated with a recent change in weather. For example, if a heavy snowfall is followed by bright sun, then the exposed layer will melt and refreeze into slick ice. If another heavy snowfall comes, then there will be a distinct layer in the snowpack that will be prone to avalanching. According to the US Northwest Avalanche Center, other dangerous conditions include shallow snowpack and very cold temperatures; bright, cold days with light winds; deep wet snow and cold temperatures; or variable winds and rain.

In general, the risk of avalanche increases with precipitation, temperature and wind strength. Avalanches can be triggered directly by gravity pulling on the layers, by falling pieces of ice or rock tumbling off the mountain, or even by the activity of a skier or snowmobiler. Avalanches can begin at points, and grow as they move down the mountain, or they can slide off in large slabs. Both are deadly, but the slab avalanches are responsible for most fatalities.

A Serious Science

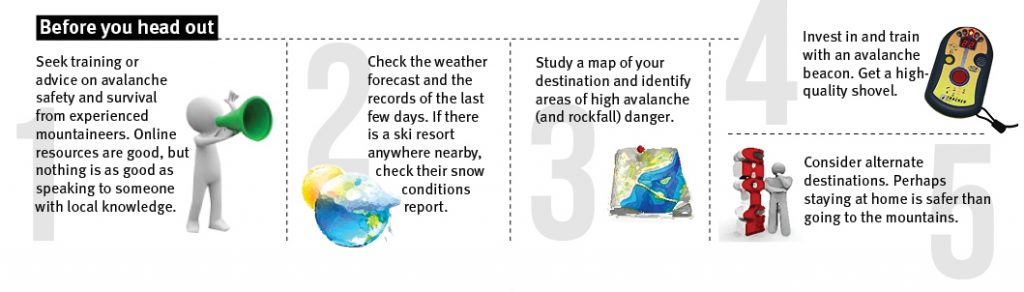

Predicting and controlling the risks of avalanches is a serious science, and is especially important for road and rail transport, skiers, snowboarders, snowmobilers and climbers. The conditions we observed on that summer’s day were a textbook example of high-risk conditions. We did, however, have the advantage of a formal avalanche conditions report provided by the climbing rangers. Reports are often available from national-level meteorological agencies, transport authorities, and from the ski patrol at resorts. These groups often have some artillery on hand that they will use to knock down dangerous portions of snow and reduce the risk.

In Asia, one particular location notable for dangerous avalanches is Sakhalin Island, just north of the Japanese mainland on the Russian east coast. Here, low rolling mountains and hills are hit by large amounts of heavy, moist moisture and a thick snowpack results. Researchers publishing in the Journal of Glaciology [Podolsky et al., J Glaciol 60: 409–430 (2014)] found that the timing of these avalanche deaths matched periods of recent immigration. The new arrivals did not recognise the danger on such gentle slopes, and had cleared the hills of the forests. These tragedies, like so many others, were linked to the destruction of natural vegetation and the lack of local knowledge and long-term historical perspective.

However, avalanches are rarely a risk for settlements, roads and facilities. When several people get together to build, the signs and possibilities of avalanches are often discussed. At greater danger, though, are small independent parties. In particular, wilderness skiers are often exposed to avalanche dangers in unknown terrain. Many fatalities have been triggered by

However, avalanches are rarely a risk for settlements, roads and facilities. When several people get together to build, the signs and possibilities of avalanches are often discussed. At greater danger, though, are small independent parties. In particular, wilderness skiers are often exposed to avalanche dangers in unknown terrain. Many fatalities have been triggered by

the unfortunate party, rather than by a chance event.

Unfortunately, avalanche victims are more likely to perish than survive. Besides the kinetic energy, hypothermia and suffocation are clear dangers. Radio-transmitting location beacons and high-quality snow shovels can help companions dig out their friends – provided there are enough friends, enough equipment and everyone has practised. The best way to survive an avalanche? Don’t be on the mountain when one occurs!

Many mountaineers will speak of subjective dangers, such as exhaustion, lack of experience, or undue haste, as something different to the objective dangers, such as rockfall, cold temperature or avalanche. To expose yourself to objective risks by choice is actually a subjective decision. We returned home for several days and came back the following week. The avalanche slabs had slid down and shattered on the lower slopes, and a few days of sunshine had helped to consolidate the snowpack. On the summer solstice, we climbed safely

on solid, consistent snow to the summit of the mountain.

For more stunning stories and photographs from this issue, check out Asian Geographic Issue 109.