In Afghanistan, a woman dies every 27 minutes from pregnancy-related complications. At 6.5 percent (6,500 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births), the maternal mortality rate in Badakhshan Province is the highest in the world.

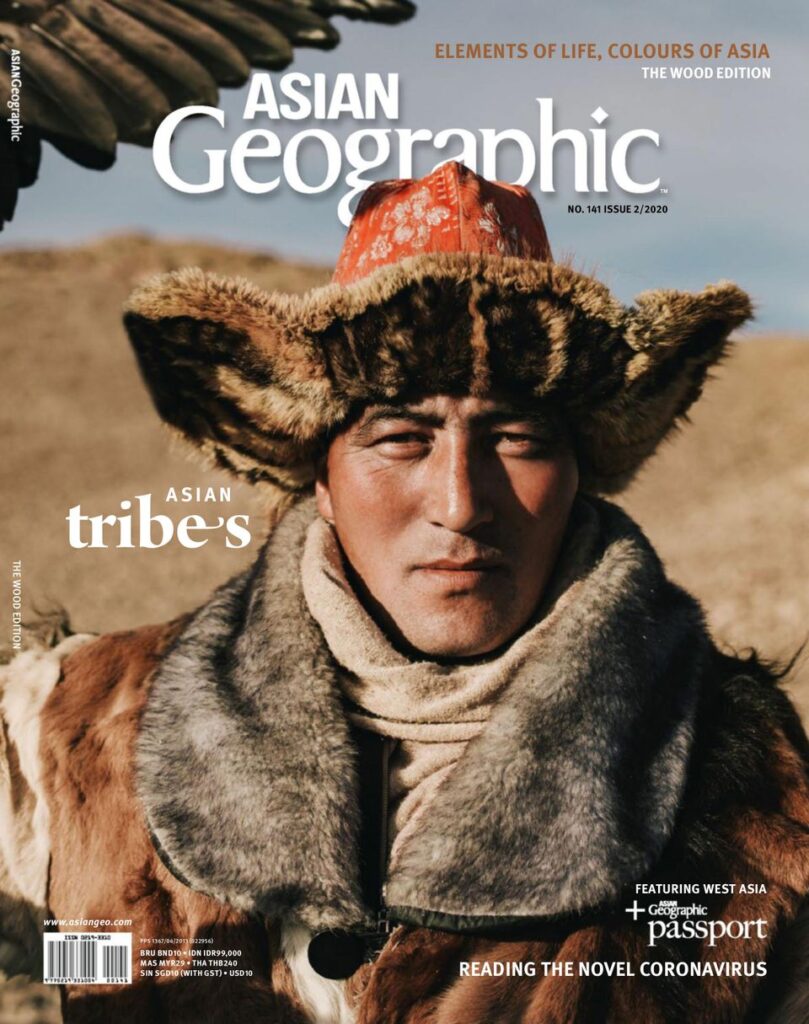

Original text by Sophie Ibbotson & Max Lovell-Hoare (AG No. 141 02/2020)

Adapted for online publication by Goh Pearl Lyn

Over the course of her lifetime, an Afghan woman’s chance of dying in childbirth or from pregnancy complications is one in eight, compared to one in 8,000 in the developed world. There is nothing poetic about these deaths; the birth of any child is a miracle, but in Afghanistan, it often comes at too high a price.

With a steady decline across the years in nominal per-capita GDP of just US$580, Afghanistan is one of the poorest countries on Earth. More than three decades of conflict with forces both external and internal have ravaged what infrastructure there was, with limited coverage in conflict-affected areas.

As the United States reduces its military presence in Afghanistan while the Taliban takes over rapidly, Afghanistan is a waiting game. And for Afghan women, the waiting game is agonising.

The nightmare of extreme and oppressive misogyny in the 1990s is soon becoming a reality again. The requisite female uniform for Taliban rule was immediately snatched up in stores by women to avoid the Taliban’s attention, and overnight, women were barred from going outside.

Women in Afghanistan everywhere currently face extensive and damaging exclusion, even if restrictions do not go as far as the total ban of the 1990s. This could mean the much-needed health aid will be harder to reach not only the rural poor in Afghanistan’s remote, mountainous regions, but also women in conservative communities under Taliban rule who rarely, if ever, leave their homes and can have no contact with men outside their immediate family.

One of the most cost-effective ways of reaching out to these populations, and an invaluable weapon in the war against infant and maternal mortality, is Afghanistan’s growing army of trained midwives.

In 2002, Afghanistan had just 467 trained midwives, and less than half of all healthcare facilities had any female staff. In Nuristan – albeit an extreme case – male healthcare workers outnumbered female staff 43 to 1. Refusing to be seen by men, even women that could physically reach medical services could not then be treated, contributing significantly to the death rate.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends one midwife be available for every 175 women of child-bearing age. To reach this goal, Afghanistan requires almost 5,000 midwives, and for cultural reasons, the vast majority of them need to be women.

The Afghan Midwives Association was founded in 2005, and funding for training programmes is coming in not only from the Afghan government but also from the European Commission, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the World Bank and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Two types of training programme are up and running and have already started delivering qualified midwives into the field.

“We will only understand the miracle of life fully when weallow the unexpected to happen.”

-Paulo Coelho (Brazilian lyricist and novelist)

The Community Midwifery Education Programme recruits candidates from areas where there is an acknowledged shortage of healthcare provision, and requires them to commit to returning to the same district on completion of their course.

Their training is principally vocational, lasts 18 months and is designed to be flexible enough to fit around other commitments, such as caring for family members or continuing to work. The intention is not to remove women from their communities but rather to equip them with the expertise to work knowledgeably and safely.

Slowly but surely, it seems to be working. In the first six years of the programme, the number of midwives in Afghanistan increased almost fivefold. Over the last two decades, the increasing presence of midwives has started to play a role in improving a mother’s and baby’s chance of survival.

Afghanistan’s problems are not going to change overnight. It remains one of the most dangerous countries in which to be born – and in which to give birth. More medical professionals are required in every specialisation, not just midwifery; infrastructure needs to improve so that people who need medical expertise can reach it, whether it is offered in a large, modern hospital or a village clinic; and gender-based barriers, be they in place for religious, cultural or historic reasons, need to be minimised to give women more equal access to care.

Afghanistan’s midwife angels may have started to fly, but their heavenly host must continue to grow and be politically and financially supported if they are to meet their worthy goals.

Read further Afghanistan’s Army of Angels by Sophie Ibbotson & Max Lovell-Hoare in AG No. 141 02/2020 here or download a digital copy here! The latest issue is coming to shelves soon, look out for it or reserve your copy today by emailing marketing@asiangeo.com