An apparent contradiction, Chinese communism has thrived as a market economy and situated the most populous country in the world as a rising superpower. But can it last?

Text and Photos Zigor Aldama

Don’t say “communism” – say “socialism with Chinese characteristics”.

That’s the official euphemism to describe China’s apparently contradictory social, political, and economic system: a one-party state with an all-powerful government which controls the judiciary and the National Assembly, and a thriving market economy where rapidly growing private and foreign businesses have to bear off-limits sectors where state-owned enterprises (SOE) benefit from monopoly or oligopoly structures.

It’s also a country where all land belongs to the state, and citizens pay for the right to use that land for 70 years. But, rampant speculation is blowing the property bubble bigger than ever seen before in China’s real estate market. The cocktail is being shaken up: Individualism and consumerism have given the boot to old-fashioned fraternity and collectivism.

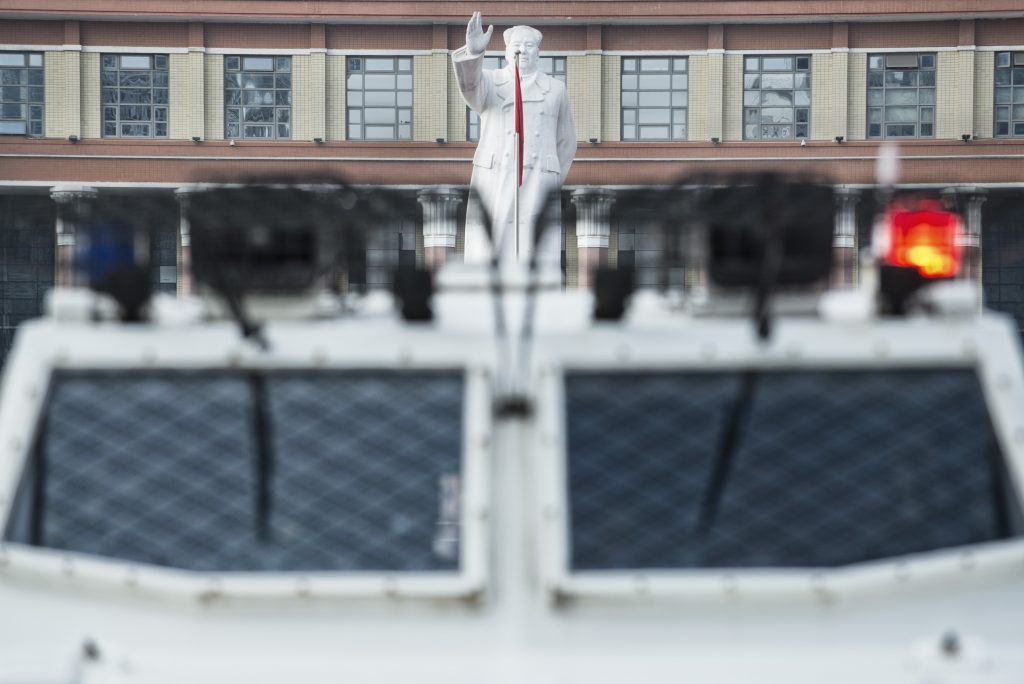

“Getting rich is glorious,” Deng Xiaoping said when he decided to get rid of Mao’s most controversial and extreme interpretation of communism, implemented first with the Great Leap Forward (1958–60) and during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). By 1979, an impoverished China opened its heavy doors to the world.

But not fully. It needed capital and know-how and foreign companies didn’t doubt that for a second: They entered in hordes to explore a cheap manufacturing base and to pioneer their business given the huge potential market for their products.

In exchange, China got everything its leaders wanted: Protecting core sectors and enacting laws that required foreign companies to establish themselves in the country with joint ventures was a perfect means of achieving the transfer of technology.

Almost four decades later, this strategy has paid off. China is the second-largest economy in the world – the first if purchasing power parity (PPP) is used; it is the main trade power with the biggest surplus in history, and the factory of the world. Moreover, with the help of the government, China has created a group of huge companies with the ambition of going global, shaking up the world order.

The Communist Party has reigned over different problems of the market economy – the real estate bubble, for example. It has set rules to make it more difficult for speculators to manipulate the market. The same goes for stocks, where the real value and market value of companies were a world apart. The situation required an adjustment, and Beijing didn’t hesitate. Their wisdom is preventing a crash like the one in the US a decade ago.

-Pedro Nueno,China-Europe Business School

Working in much the same way as Japan did in the 1980s and 1990s, Chinese companies are producing products with similar features to those from their competitors – at cheaper prices – to gain market share in a world burdened by the economic crisis.

And, thanks to their huge consumer base at home and China’s reserves (at USD3 trillion), they have started to buy foreign companies: Huawei telecommunications and electronics, Lenovo computers (owner of IBM), Geely cars (owner of Volvo), Wanda real estate (owner of America’s largest theatre chain, AMC), PetroChina Oil (owner of 50 percent of Singapore Petroleum), Li Ning Sports Apparel (owner of Kason), CNR Trains (with multiple contracts for high speed railways) and COMAC commercial aviation (with close to 1,000 orders for its new ARJ-21 and C919 jets) – these are just a few of the names making headlines worldwide.

The statistics painting the picture of China’s economic miracle are astonishing. Their compromise to embrace a market economy in tandem with socialist ideals leaves analysts to ponder whether China can remain classified as a communist country.

It’s a heated debate. Xu Bin, Associate Dean of the China-Europe Business School (CEIBS) in Shanghai, elaborates: “It has features of both systems. It’s a hybrid. And we can argue that China has beaten the West at its own game with the weapons designed by traditional colonial powers to keep their supremacy,” he says.

“Communism doesn’t equal poverty, or lack of ambition. We still have features of a planned economy, like state-owned enterprises, and a social welfare system which, despite its flaws, has lifted hundreds of millions of people – 400 million according to the United Nations – out of poverty, and gives at least basic assistance to all in need.”

In fact, China’s per-capita GDP has almost tripled since 2002, while many Western powers have seen theirs decline due to the global financial meltdown. That, Beijing argues, shows that China’s system works.

Communism doesn’t equal poverty, or lack of ambition. We still have features of a planned economy, like state-owned enterprises, and a social welfare system which, despite its flaws, has lifted hundreds of millions of people – 400 million according to the United Nations – out of poverty, and gives at least basic assistance to all in need.

-Xu Bin, China-Europe Business School

Pedro Nueno, president of CEIBS and professor at Spain’s IESE Business School, agrees: “Chinese people live much better now than they did 20 years ago. The fact that labour is much more expensive may deter some businesses from setting up camp in China, but it’s a huge victory for a country where domestic demand is driving the economy, rather than exports and foreign investment. Some say China is in trouble because it has grown at its slowest pace in the last quarter of a century, but I say a well distributed growth of five percent is much better than a concentrated eight percent.”

Nueno believes that Chinese leaders are among the smartest in the world. He defends the claim by explaining how they use another characteristic of communist states: government intervention. “The Communist Party has reigned over different problems of the market economy – the real estate bubble, for example. It has set rules to make it more difficult for speculators to manipulate the market. The same goes for stocks, where the real value and market value of companies were a world apart. The situation required an adjustment, and Beijing didn’t hesitate. Their wisdom is preventing a crash like the one in the US a decade ago.”

But not everybody likes this. Asked about the protectionism that the American and European Chambers of Commerce criticise in their annual reports, Xu says: “It’s not something exclusive to China. The US – especially with Donald Trump in charge – and the European Union subsidise their companies, contravening World Trade Organisation regulations. They’re right to demand more economic reforms, but they should also acknowledge the market economy, and the profound reforms of China.”

Macroeconomics aside, Chinese millennials – born long after the Cultural Revolution – are the most confused about the meaning of communism. “They teach us a theory that has nothing to do with reality. The Mao we love the most is the one printed on 100 yuan bills,” jokes Chen Qing, a 25-year-old salon stylist. “We have an entrepreneurial heart, but sharing is not one of our strong features.”

Zhu Liya, a 26-year-old owner of a pearl trading company, adds: “Communism as imagined by Marx or Mao doesn’t fit Chinese people.”

The Mao we love the most is the one printed on 100 yuan bills. We have an entrepreneurial heart, but sharing is not one of our strong features.

– Chen Qing, 25

Ding Chen, a purchase manager at a foreign-owned engineering company, doesn’t see China as a communist country either.

“It’s just an authoritarian government with a capitalist economy where laws protect leaders’ businesses,” the 30-year-old says. “That explains why the gap between the rich and the poor is widening, and [why] China is drifting away from the Marxism ideal of a classless society. But, we can’t say anything about the corrupt and the fuerdai [the second generation of the rich in China] because you may end up in jail. I’ve had to leave China to understand what free speech and other human rights are. Communism should grant those, but it doesn’t.”

Chen adds that the government says – and makes Chinese people believe – that China is already a democracy. “A Western-style democracy wouldn’t work because we are too many, and China would collapse. But that’s just pure speculation,” he says with a shrug.

The leaders say that our country has the rule of law. But that’s just a plain lie. The Communist Party controls all power and doesn’t care for human life.

-Ai Weiwei, exiled artist

Prominent artist Ai Weiwei is also highly critical of the political reforms in China. “The leaders say that our country has the rule of law. But that’s just a plain lie. The Communist Party controls all power and doesn’t care for human life,” he says.

Ai’s words – along with his most controversial artworks – landed him three months of detention, but that won’t keep him quiet. “The Internet has brought a lot of changes to China. Even though censors try their best to keep it under control, it’s still a breath of freedom,” he says.

Ai hopes that the new generations will use it wisely to push for democratic reforms “which haven’t tagged the economic ones along”.

But stiff penalties are imposed upon those who “subvert the power of the state”. Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo knew this well: He was sentenced to 11 years in jail for demanding democracy for China.

Even though political reform is not on president Xi Jinping’s agenda, the central government is committed to deepening economic change. Now is the time for state-owned enterprises

(SOEs) – one of the last strongholds of true communism in China.

These companies produce far more than the country – or even the world market – needs. For example, China’s SOEs produce so much steel that when prices fall, the rest of the world cowers. SOEs are primarily a source of jobs and, as such, profitability is not a priority.

“Not only are they a burden for the country, but they are also unfair for the world. They are protected in China, where no competition is allowed in their sectors, but they [also] enjoy a level playing field elsewhere,” says Carlo D’Andrea, Vice President of the European Chamber of Commerce in China.

Related: China’s One Belt One Road

Related: Made in China

Still, for millions of workers, SOEs represent a stable job market with many of the benefits you would expect in a communist country – free housing, for instance.

SOEs make up only three percent of all Chinese companies, but they produce up to 40 percent of all industrial output, employ around 37 million people, and generate around 20 percent of the GDP.

“We still have many advantages over those in the private sector, which make more money. That’s why many wish to work for SOEs. But things are changing. Before, we knew our jobs were secured for our whole life,” says Hu Xiong, an employee at one of the biggest steel companies in China.

Now, Hu is worried, because almost two million people will be laid off in coal and steel sectors. “They say we will be relocated, but we know that many will lose their jobs. Without other skills, we don’t know what to do,” he says.

Before, we knew our jobs were secured for our whole life. [Now] They say we will be relocated, but we know that many will lose their jobs. Without other skills, we don’t know what to do.

-Hu Xiong, steel SOE employee

The Communist Party of China with Xi at its helm feels stronger than ever. Those interviewed agreed that although its fall has been predicted in the West many times since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, a change of political rule is highly unlikely. The respondents also felt that there will be a faster shift towards capitalism and, thanks to Donald Trump’s policies, a huge increase of Chinese influence globally.

“We must oppose protectionism and facilitate both free trade and investment,” said Xi at this year’s World Economic Forum. His words left many speechless.

… China is drifting away from the Marxism ideal of a classless society. [The government says] A Western-style democracy wouldn’t work because we are too many, and China would collapse. But that’s just pure speculation.

– Ding Chen, 30

But it makes sense. China needs to expand. The state is flexing its muscles, exerting its influence in the developing world with new initiatives and agreements – such as the BRICS (the association of five emerging economic powers: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and One Belt, One Road (a huge infrastructure programme, initiated by Xi Jinping, linking China with Africa, Asia and Europe via roads, railways and ports) – in which the US don’t take part.

China has also set up international institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) which will help fund Beijing’s international agenda.

As Xu Bin puts it: “China is just regaining the place it deserves on the world stage.”

For more stories on Asian politics, see Asian Geographic Issue 04/2017 No. 126